Anthony Reid remembered Malaysia and the 1969 riot

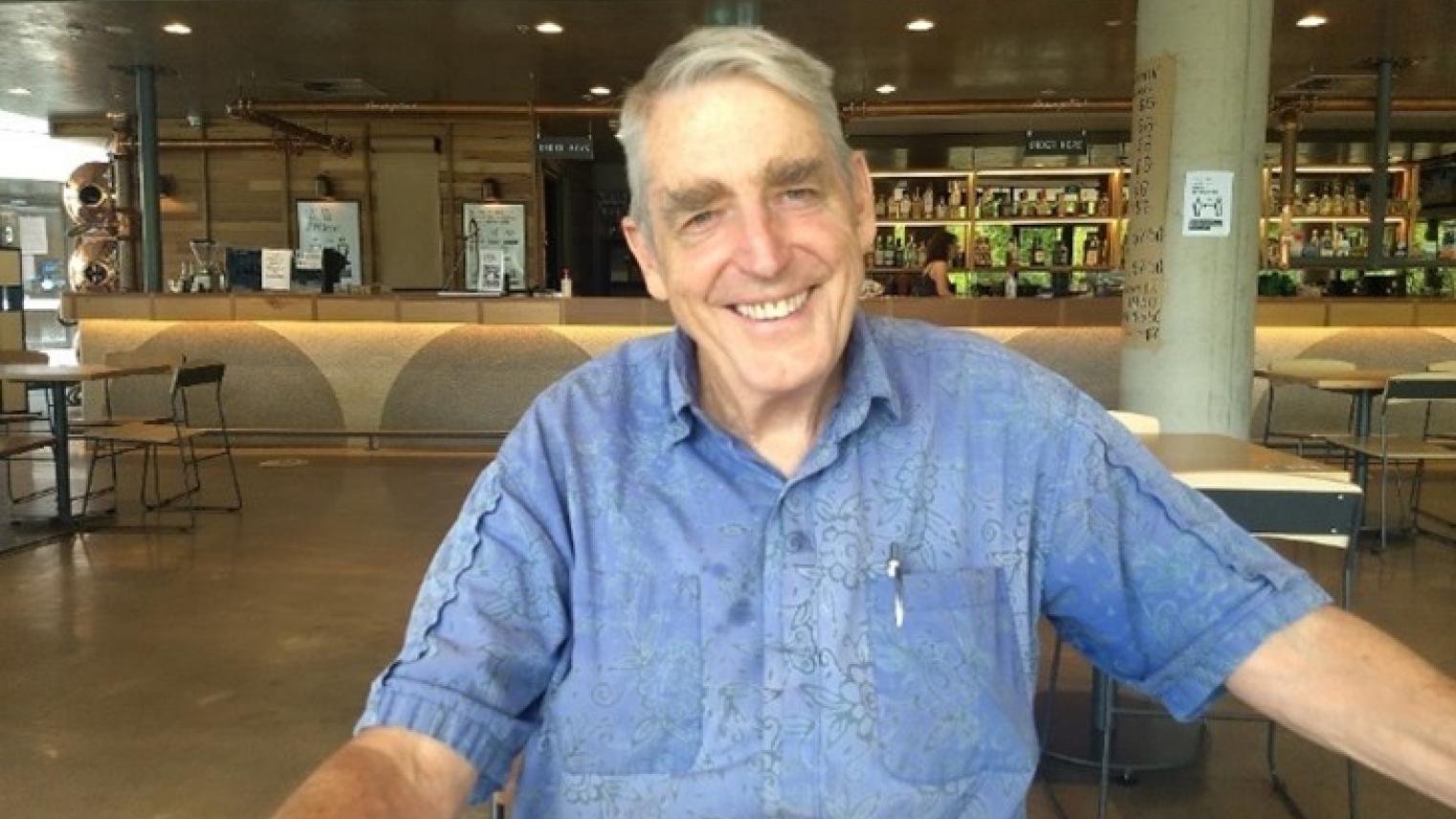

Born in New Zealand in 1939, Anthony (Tony) Reid was a world-renowned historian of Southeast Asia and Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University (ANU). He passed away peacefully in Canberra on 8 June 2025.

Although widely recognised and self-identified as an Indonesianist, Tony’s first scholarly experience with Southeast Asia began in Malaysia. After earning his PhD from Cambridge University, he took up his first academic post as a Lecturer in the History Department at the University of Malaya (UM) at the age of 26. He arrived in Kuala Lumpur with his wife, Helen, in 1965, and they lived in faculty housing in Petaling Jaya. When the May 13 racial riots erupted in downtown Kuala Lumpur in 1969, Tony volunteered to help distribute emergency supplies. In the months following the unrest, he published one of the earliest scholarly analyses of the incident, titled “The Kuala Lumpur Riots and the Malaysian Political System”. He left UM in 1970 to join the ANU, amid sweeping changes in Malaysia’s political and educational landscape.

In November 2020, Ying Xin Show, Deputy Director of the Malaysia Institute, interviewed Tony about his time in Malaysia and his firsthand account of the May 13 riots. This oral history was later published in the book Life After: Oral Histories of the May 13 Incident by Gerakbudaya in 2022. Its Malay edition was published in 2025. With the editor’s permission, we are republishing this story online in loving memory and honor of Professor Anthony Reid—an extraordinary scholar whose contributions profoundly shaped the study of Southeast Asia.

Arriving Malaysia in 1965

I was a Lecturer in the History Department of the University of Malaya from 1965 to 1970. That was my first job, a very exciting first job. I came with a Cambridge PhD in History on the Aceh war, so was of course especially interested in Sumatra. But the contrast with Malaya was a theme that interested me all the time, noticing that the Sultans were such a big deal in Malaysia, while in Sumatra they’d got rid of them rather bloodily. I began as pretty much a tabula rasa about Malaysia and, of course, was amazed at just how I’d landed in this special place where everything happened. In no time Singapore was thrown out of Malaysia in my first year. It was a very exciting period.

I first reached Malaya at Penang because my wife and I had travelled overland from Cambridge to Madras, Chennai. And in Chennai, we put our Kombi van on the SS Rajula to Penang. Penang was the place I’d been studying intensely; it was a central place where the British and Dutch intersected in the contest about who was going to dominate Sumatra and Aceh. The resource supply base for the Dutch army was in Penang, and it was the Aceh window of the world as the richest Acehnese had houses in Penang, and their pepper trade was with Penang. So, for me, arriving by ship was the exciting moment to see these places I’d been reading about. I had to be up on deck early to sniff in every smell, seeing it all as my Acehnese would’ve seen it coming from the port. Then we took our van and started driving it down to KL. We were both sick with hepatitis and really needed to find a base to get medical attention.

Thank God, the University of Malaya was very generous. They put us up in the Majestic Hotel for a few days, which was very nice, and then gave us a pleasant transition house in Section 16 in Petaling Jaya. I think it was called Lorong 16/1. At first, we were quite isolated because we were too sick to do anything. My wife soon went into the hospital. There was a period of a few weeks when a Chinese neighbour was our main local contact. The other was a sweet guy who came around trying to sell us insurance (laugh). We talked so much to him because we wanted to know everything about Malaysia. And we ended up buying his insurance just because it was so nice to have this visitor coming and telling us what we needed to know about Malaysia.

The year was very exciting and the History department was a good window onto things. I really enjoyed my colleagues and of course, everybody was either Malaysian or had been there longer than me. So, everybody knew things that I didn’t and I was just absorbing everything. Always, everybody, whatever ethnicity or background, had a different take on the world. That was very interesting.

The day the riot broke out

On May 13th, we were going to have a History Department dinner. It was a tradition that Wang Gungwu established and he did very well in organizing all the best Chinese restaurants, including the Muslim Chinese restaurants. The Mah family restaurant was a favourite. I forget which restaurant it was at the time, but I remember it was in Ampang road. We were probably going to farewell or welcome somebody.

John Drabble, who wrote the Economic History of Malaysia, was a colleague who arrived after me, with his Malaysian Chinese wife. Once we had children we were given a bigger University house quite near the entrance of the University onto Jalan Universiti, and they were neighbours in a similar house next door. I think we were going to give them a lift to the 13 May dinner. And then the first thing we knew was a phone call from our Malay colleague Zainal Abidin Wahid who said, ‘You’d better not go. There’s trouble in KL’. He didn't say much more than that, and I tried to tell some other colleagues whose phone numbers he probably didn’t have. Only two people, who didn't know what was going on, went to the dinner. Our Malaysian colleagues probably knew from contacts that things were falling apart, but not the more ‘expatish’ of the expats, if you like, who weren’t studying Southeast Asia. The two were David Routledge, who got his PhD at the ANU on Pacific Islands history, and Roman Dubsky, a Canadian Hungarian who taught European history. They were both bachelors, so maybe not networked in the same way. They both went to the dinner and the guy at the restaurant started serving them a meal. But after a while, they saw flames outside as the place was just across the road from Kampung Baru. The restaurant guy didn’t offer any help so they tried to get home themselves. Maybe one had a car and the other had a scooter. They were faced by military roadblocks and had guns pointed on their face. One of them ended up in the PJ police station for the night.

At home, we were glued to the radio, as nobody had a television. There were very unsatisfactory reports, playing the violence right down, but exaggerating the provocation from opposition parties. We talked to our neighbours and we must have exchanged rumours with a couple of other friends by phone. A colleague Steve Leong remembered that he came and played badminton with us during the curfew, but I don't remember that we were allowed to do that. I got in touch with John Drabble recently and asked what else he remembered of the curfew. He said, ‘Yes, we were there at your place, and we were very grateful for the chicken that was delivered by the university to help us survive’. He said the university had an Agriculture faculty with a chicken farm, and that they tried to help the staff by killing the chickens and sending them around. I didn't remember that at all, but maybe that’s true.

I volunteered to distribute food and saw a body

During the curfew, we just stayed at home. We started to hear on the grapevine that a lot of Chinese had been killed. Probably on the 15th, I heard from the radio that they need volunteers to help distribute emergency supplies, so I rang the number that had been mentioned. I was extremely eager to find out what on earth is going on. I was amazed that they did come to pick me up! They didn’t blanch at my foreign name. I had no idea what organisation was behind that; but they must have had authority to move about despite the curfew. I got onto the back of this truck with three or four other people, where there were bags of rice, and we went to places in downtown and we heaved the bags of rice off at different places. I have found one photo I took, it’s just an empty street with burned-down houses and shophouses. But I did see one body on the road, of which I didn’t dare take a photo. I assumed he was Chinese, facing down.

That was the only time I was on the street during the curfew - only for a couple of hours - and they didn’t say they will come back tomorrow.

Ethnic relationship changed

I do remember, maybe long after the curfew was lifted, there was a Russian guy from the Soviet embassy saying, ‘What’s wrong with this country? Why don’t they bring in the British troops? This is practically a British colony, so they should sort it out!’

One of the troops in charge that we were aware of and people had cheered for was the Sarawak Rangers. I think they brought in the Sarawak Rangers because it was the only military unit which wasn't all Malays. The military had proven that it could not be impartial, that they were shooting the Chinese. I think that was known. The evidence was reported that when people took the early victims to the hospital, they had suffered from parangs (machetes), but later it was guns. The Chinese were being killed by gunfire, so clearly it was the military. Therefore, someone was wise enough to bring in Sarawak Rangers, as the latter were probably predominantly Iban or at least mixed and were presumed to be neutral. People were really saying, ‘Thank God the Sarawak Rangers are here’.

During the upheavals in the 1960s, the riot squad unit (FRU) had been controlling Left-wing demonstrations which were predominantly Chinese, and they seemed to assume that the Chinese were the bad guys and communists. During the riot, they were proven to be inexperienced in dealing with a large group of Malays which included some middle-ranking UMNO members.

By banning all press coverage, declaring a state of emergency, suspending Parliament, arresting almost exclusively Chinese and blaming the victims, personified as communist agitators and opposition politicians, the government lost all credibility among the non-Malay population as well as foreign journalists. One could feel in the streets that the former empathy between Malay and European in common worry about Chinese communism was almost overnight replaced by empathy between non-Malay as victims and the foreign observers. Before 1969, one was always amazed at when you go to kampung, how friendly and polite and nice the Malays were, in contrast to often relatively rude Chinese. It was a similar experience for many foreigners. And that changed. It really changed.

University reopened and the path it took

I am not sure exactly when the university reopened, but to me, it wasn’t all that long. Once we were back, we used to have morning coffee or tea at 10 o’clock every morning in the library of the department.That’s where all the gossip went on.

There were lots of talks. Rumours continued for quite a while, saying there were more killings. I think there was an outbreak maybe a week or two later in Sentul because I seem to remember there were grizzly photographs of bodies, both Indians and Chinese. Steve Leong, the neighbour we played badminton with, I think may have had family in Sentul.

I remember teaching some classes and some people were still a bit shell-shocked by that whole experience. There was one Malay student in my class, talking about people who are “kebal” (invulnerable), about certain mystical practices. Suddenly, he said, people who knew about silat (Malay martial arts) became leaders, and these martial arts became very popular. Everybody wanted to study them and suddenly there was an interest in violence. Since this is the closest I ever came to experiencing the potential for violence that lurks beneath the sopan (polite) and rukun (harmonious) surface of Southeast Asian life, it helped me to write about the suicidal violence that surfaced in the Indonesian revolution in particular.

In university, very quickly there were changes. Before this, there had been a tendency to delay the implementation of the Malay language, as the university was quite reluctant. How were the engineers going to teach in Malay? They had no idea, and with zero Malay faculty they didn’t take the challenge very seriously. Of course it was easier for us in Arts. They finally solved the problem with getting even the engineers to attend Malay classes by putting the most gorgeous of the Malay lecturers in charge of the course that they put on for the staff.

I didn’t have to lecture in Malay in that transition year (1969-70), but I did seminars in Malay. I believe almost nobody except Zainal lectured in Malay. In the Arts faculty, it may have been imposed immediately that we had to allow students to write their assignments and exams in Malay. It was a useful challenge for me to have to examine the papers in Malay, since I had been working on my Malay. Generally the Malaysian lecturers could also do that, or if they couldn’t they had to pretend that they could. But some lecturers really couldn’t, so I think other tutors or somebody had to read the exam papers and essays for them.

I remember I was struggling a bit with all these essays and exam papers and feeling that I was probably being very generous. Sometimes when the writing didn’t seem to make sense I would think, well, maybe their Malay was better than mine so would not have the confidence to mark it down. I was aware at the time of the unfairness. When students wrote in English I couldn’t help myself but correct the language. It’s just instinctive. Although it’s a history subject, language does make a difference in whether you make a point well, or you’re clumsy. So, I think the Malays probably benefited from choosing to write in Malay.

The end of the cosmopolitan phase in UM

I left in January 1970, and the next year would be a further step. Even before I left, a lot of these changes were starting to take place. I wrote a letter to Nicholas Tarling on 14 July 1969, talking about how ‘the young Turks’ had taken over and they felt they had the bit between their teeth:

The events of the city appear to have been echoed in interesting ways in the university - not in bloodshed, thus far, but in terms of more radical and militant solutions being sought to problems. There appears to be suddenly a sense of urgency that if the nationalist bandwagon is not jumped on now it will career out of sight. The ‘young Turks’ have got control of the Faculty and are making things difficult for the professorial establishment at the moment, and the effect on foreigners wishing to teach in the Arts Faculty is likely to be difficult for the next few years until things quieten down or a new group comes decisively to power.

Where possible, Malay lecturers were thrust prematurely into leadership in the hope of better controlling if not satisfying aggressive and politically-connected students. Only in the Arts Faculty could this be feasibly done at once. Hamzah Sendut (Geography) and Taib Osman (Malay Studies) became Dean and Deputy Dean of Arts, Mokhzani Head of Economics and Tengku Shamsul Bahrin Head of Geography. The determination to control this Faculty in particular so as to make the maximum number of Malay appointments and admissions to it necessarily resulted in a lowering of international-type standards to a degree that might have been avoided in a more gradual shift.

When Wang Gungwu had moved to Canberra (late 1968), the University had replaced him as Professor and Head of History by the formidable young Sri Lankan Tamil historian Arasaratnam, already doing well in UM’s Indian Studies Department. It had seemed an excellent choice to most of us, but not being a Malaysian citizen made him an easy target after May 13 for those who wanted to accommodate Malay demands. Although the few professors in the university had been automatically heads of their departments, he was told to step down as head the day after returning from leave in July 1971 in favour of Khoo Kay Kim. That was also the end of hiring foreigners into the Department. Leonard Andaya and Heather Sutherland had been hired by Arasaratnam but arrived at about the time of his fall, and were excluded from Departmental meetings. Their departure in 1974 ended that cosmopolitan phase.

The young Turks were also unhappy about the English department, asking why do we need an English department. But those days lot of kids came through English medium schools and were passionate about Keats and Shelley, such as the writer Shirley Lim. Historian Wang Gungwu also came through that track and wanted to be a writer. Trendy people often did English, and they wrote these daring things. I supposed later the English Department became more dragged down by having to teach people basic English.

After May 13

Frustrated at being stuck powerlessly at home while these horrific events unfolded, I decided all I could usefully do was write the whole issue up, at first to channel my despair, but gradually to seek to understand and explain. I wasn’t a journalist writing about what happened on May 13th, I was supposed to be a historian to make sense of it all. So, I started reading other things and doing a few interviews. I can’t remember who else I interviewed besides Dato Harun, because I thought he was the one I especially should interview. But when I looked again at the article, it doesn’t seem as if I got anything useful out of that. I can’t remember how did I get him. Could be through Zainal or maybe I just rang up at his office. I went to his place and I believe it was the same place that the UMNO crowd gathered when the riot happened.

I had completed this article by July, as the direction of post-crisis government became clearer under the new leadership of Tun Razak and an extra-parliamentary National Operations Council (NOC). I concluded that the fundamental shifts in policy were all in the direction of shoring up support for government among younger urban Malays. The changes were: 1) immediate beginning to the staged replacement of English by Malay instruction (though allowing Chinese and Tamil schools to continue); 2) return of a Parliamentary system on condition that the sensitive issues of Malay privilege could not be discussed; 3) a shift from rural to urban employment schemes for young Malays, through rapid establishment of labour-intensive industry. The mood was far from optimistic that this kind of policy would overcome the collapse of confidence in government and interracial cooperation. For months Chinese avoided Malay food stalls. Many thought of leaving. The University was also caught up in the radical shift in a Malay-nationalist direction.

For six months, we talked about nothing else except for the riot. I was so grateful that I had already decided to go - I had been negotiating with the ANU before that. I got a cable from them on 2 June, saying that in case I was ‘under any feeling of anxiety or stress’ in view of the riots and was worried about the future, they were speeding up the process to tell me that I had got the job. There were just a few nominal committees to go through. In Feb 1970, I moved to Canberra.

The article ‘The Kuala Lumpur riots and the Malaysian political system’ was later published in the Australian Outlook journal. I thought since I was going to Canberra, maybe I should begin to publish in Australia – although I seldom did so again. The consequence was that not many in Malaysia read it, and I didn't get any feedback from anybody.